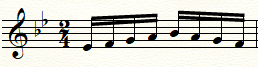

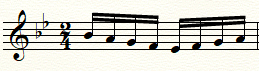

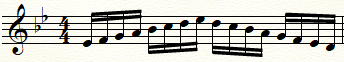

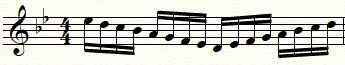

Now we get to the details of the page itself. Generally, as you are learning the piece, you should be paying attention these things as much as you can. However, these aspects can be a lot to focus on at once, so they can be tackled after you've established the notes and their execution. You want to make sure that the rhythms you are playing are correct, for obvious reasons, but it also ensures that you are not rushing or dragging during your performance. It's not only the fact that you are playing a sixteenth note, but that you are giving that sixteenth note its proper length. Next are the dynamics. In the first pictured example, the dynamics are shown to be based on the accented and unaccented notes (accents getting a fortissimo marking, and unaccented notes a mezzo forte marking.) In this example, this remains the same, but the second measure has a diminuendo poco a poco (get softer little by little.) You will have to take this into consideration when gauging the dynamic difference between the accented and unaccented notes as they get softer through the remainder of the excerpt.

Next are the embellishments and articulations. For this piece, the sheet music only gives accents, but that doesn't mean there are no other articulations to consider. Listening to the piece, is the over all texture articulate, legato, something in between? The answer to that question informs the general articulation that you will use for the excerpt. After that, anything written in the piece adds on to that. Personally, I wouldn't play this too staccato, or short, but not too long either. Something clear but with a little bit of length. Here, there aren't any embellishments, but in a piece like Messiaen's Exotic Birds for instance, taking care of the sound and execution of the embellishments really livens up the piece, and gets it that much closer to being a more complete product in the end.

Memorization

This is kind of an extra step. You don't necessarily have to memorize everything that you learn, but this step occasionally happens naturally as a result of your work on and repetition of the piece. There are many ways to intentionally memorize a piece. Links to two other options can be found here and here. Here are some tactics that I have used.

Playing each bar until I feel comfortable, and then playing it without looking at the music

Singing each bar as I learn and play them (either out loud or in my head)

Singing the part without playing (either out loud or in my head)

Visualizing myself playing (with or without the sound)

Audiating or imagining hearing the piece

Focusing on the motions I do/need or the choreography of the piece

Playing the piece with only one hand, either air playing or dropping completely the other hand

Playing the piece with my eyes closed (focuses my attention on movements and sounds)

Learning it phrase by phrase, and repeating it until it's familiar (great for Bach solos I think)

This may seem like a lot to handle at first, but hopefully seeing these grouped together this way lessens that overwhelming feeling. These aspects all influence each other in some way, and can be moved around to suit your strengths and weaknesses. I personally had a hard time with memorizing pieces starting out, but I was very good at working on my movements and intonation. So, by focusing only on that, it helped me memorize what my body needed to do to get to each note, eventually memorizing the entire choreography and consequently the piece. What are your strengths? How can that influence another aspect of your learning process? You can put your focus in those areas, and by finding those commonalities, they can help you strengthen your weaknesses.

Another example is articulations. If you have trouble executing articulations as they appear, you can think of them in a different way. An articulation influences the sound in a certain way, and if focusing on sound concept comes naturally to you, you can think of the articulation as an addition to the existing sound concept. If the physical execution is difficult, putting focus on the motions, or sticking choice could help as well. Maybe neither tactic works, and it's more of a mental challenge. You can sing, audiate, visualize, etc., wrapping your head around the event.

Knowing how you work, what you need to accomplish and knowing when something is complete will inform how long you spend practicing anything. If you know that it takes a while to learn the notes, dedicate more time to that. If you know that learning motions helps you learn notes faster, incorporate that in your practice, and that will save you time. Through trial and error, you will find your strengths and weaknesses, your habits, your personal short cuts or groupings that work together, etc. and with time you will be able to make your practice more efficient. Do not focus only on the amount of time you spend on each item, but on their completeness. If it takes you 5 minutes or 50 minutes to complete a task, that's fine. The key is to be aware of it, and know when to move on.

I really hope these tips help you in some way, and that your practice becomes more enjoyable and efficient with time. Thanks for reading!